|

|

|

|

|

|

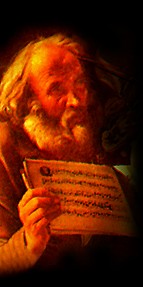

Those saints, Lord - something of them you must know?

they felt the ticketest of monastic walling

was still too close to laughter and to bawling

and dug themselves into the earth below.

Each with his breathing and his light consumed

the little air his trench had got to give,

forgot the age and features he'd assumed,and like an

all-unwindowed house would live

and died no more, as though he'd long been dead...

In a chamber round,

by fragrant silver lamps illuminated,

Those lone companions sometimes congregated

in front of golden doors and contemplated

the dream before them with mistrust profound,

and murmurously their long beards undulated...

They're shown to thousands now from town and plain,

who come on pilgrimage to this foundation.

Their bodies for three centuries have lain

Without experiencing disintegration.

Like soot from smoking light the dark piles high

Upon their shrouded forms, so long reposing

And so mysteriously undecomposing,

And their clasped hands, for evermore unclosing,

Like mountain ranges on their bosoms lie.

Rilke was fascinated with this monastery, built on the inside of a grotto near Kiev in the eleventh century, and with its monks - his Book of Hours is a poetic tribute to them. What so appealed to him was the spirit of Russian Orthodoxy, the spirituality of the Eastern Church. More removed from the world than the Roman Church, less involved in preaching than in clarifying and enlightening, it is a church whose believers look first to the themselves, in a spirit of renunciation, before they make the attempt to reform orhers.

At times, Arvo Pärt's compositions are like the Hesychastic prayers of a musical anchorite: mysterious and simple, illuminating and full of love. "In the Soviet Union once, I spoke with a monk and asked him how, as a composer, one can improve oneself. He answered me by saying that he knew of no solution. I told him that I also wrote prayers, and set prayers and the texts of psalms to music, and that perhaps this would be of help to me as a composer. To this he said, "No, you are wrong. All the prayers have already been written. You don't need to write any more. Everything has been prepared. Now you have to prepare yourself.' I believe there's a truth in that. We must count on the fact that our music will come to an end one day. Perhaps there will come a moment, even for the greatest artist, when he will no longer want to or have to make art. And perhaps at that very moment we will value his creation even more - because in this instant he will have transcended his work."

Arvo Pärt's approach to religion has given rise to a humbleness in his artistic aims - his is an attempt to fathom what is secret and unknowable, and he is aware that this will be revealed to him in untranslatable musical forms, if at all - in works which silence chooses to abandon of its own accord. Arvo Pärt's cryptic remarks on his compositions orbit around the words "silent" and "beautiful" - minimal, by now almost imperilled associative notion, but ones which reverberate his musical creations. The abbot Cyprian once described the singer Romanos - one of the legendary figures of the Eastern Church: how his wonderful, deep rooted voice began to sing words, and how a heavenly melody that poured forth with the sound of silver bells died away in the twilight of a majestic house of God.

Did Cyprian have a presentiment of Arvo Pärt's work - perhaps his Cantus? Was Arvo Pärt inspired by these sacred texts? Or is it the persistent influence of the Orthodox Church - stubbornly unchanging since 787, yet growing stronger as it perseveres - that binds the centuries together, binds the icons of yesteryear with the sounds of today? When the composer Pärt comments on his style - a style he calls tintinnabulation, from the Latin word for bells - his words sound as if they came directly from the abbot Cyprian's engravings in the golden book of Orthodoxy, "Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers - in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning.

The complex and many-facetted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises -

and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. Here I am alone with silence. I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played. This one note, or a silent beat, or a moment of silence comforts me. I work with very few elements - with one voice, with two voices. I build with the most primitive materials - with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I called it tintinnabulation."

The Estonian Arvo Pärt, who was born in Paide and grew up in Tallinn, does not come from an especially religious background. Nevertheless his piety, a type of subjective religiousity, has a connection with the type of society that now characterizes the Soviet Union - the country that where he lived until 1980. His works Credo, St. John's Passion, Cantus, Tabula rasa, Annum per annum, Frates, Missa, Cantate Domino, Summa, De Profundis - are all "works of suffering" that at the same time transcend their character. In a world in which Christian ideals are not universally acknowledged, this state of suffering (of cannot occur) is not one that must be artificially created. "It would not have been difficult for the Apostles to have lived in the Soviet Union.

And there are wonderful people like that there. Heroism can flower in that climate. But it is not absolutely necessary for people to live under such conditions. Perhaps it is more important for something ton happen within us, out of our own free will.

It makes a difference in the way one thinks if one is hungry or full. Should we all for that reason go hungry? There exists a higher level for us than just being hungry or full. We would not allow ourselves to founder on these two extreme alternatives."

Arvo Pärt's music tends to extremes. One senses its roots and its spirit, but the structure of the music is harder to grasp. A curious union of historical master-craftsmanship and modern "gestus", it is music that could have been written 250 years ago and yet could only be composed today. It is Vivaldi and Erik Satie, an impressive 'musique pauvre' thathas discarded all its structural moorings - music whose sparse tones are so intensified that any and all sense of the lackadaisical is eliminated, music that just as it is about to die away, blooms with infatuation. "That is my goal. Time and timelessness are connected. This instant and eternity are struggling within us. And this is the cause of all of our contradictions, our obstinacy, our narrow-mindedness, our faith and our grief." Musically, all the ages mingle at the break of Arvo Pärt' dawn.

Arvo Pärt began his series of orchestra works with an obituary - but one that was at the same time the start of something new. Written in the year 1959 while he was a student at the conservatory in Tallinn, Necrology is the first piece by an Estonian composer to make use of the technique of serial music - a scandal for Soviet aesthetics. And so Pärt began what was to be an eventful life as a composer alternating between periods of withdrawal in the search for a style and periods of considerable creative output. Since the early 60's, Pärt (who was born in 1935) has travelled between the extremes of official recognition and official censure. Our Garden for children's choir and orchestra (1959) and the oratorio The Pace of the World (1961) were awarded the first prize in composition in Moskow in 1962. Because of its text - "I believe in Jesus Chirist" - Credo for piano, choir and orchestra, was banned.

Until the end of the 60's Pärt earned his living in his capacity as a recording director at the Estonian Radio in Tallinn. He began working there while he was a student and wrote over fifty film scores, "There are no problems writing music for films. Perhaps because it is not under the jurisdiction of the Composer's Union. Besides, film has to go through so many filters. There's nothing a composer can do about it. The music is cut and edited together with the film - like a piece of sausage - and then stuck back together. Afterwards one's music is no longer recognizable."

Necrology was the most prominent work in a 'serial' phrase that quickly exhausted itself in Arvo Pärt's oeuvre. The principle of collage seemed to provide a solution to the technical impasse he then faced in his composing (Cello Concert, Collage on B.A.C.H., Second Symphony, Credo). After a period of stylized compositions and many tears of self-imposed silence (which he used in the study of French and Franco-Flemish choral part music from the 14th to the 16th centuries - Marchaut, Ockeghem, Obrecht, josquin) he wrote a few compositions in the spirit of early European polyphony - the Third Symphony is anexample: a "joyous piece of music" but not yet "the end of my despair and my search."

Arvo Pärt remained silent once again until in 1976 he published a small piano piece, For Alina, - a simple composition of extreme high and low notes, open intervals and pedal notes - a quiet and beautiful piece of music. "That was the first piece that was on a new plateau. It was here that I discovered the triad series, which I made my simple, little guiding rule." Arvo Pärt continued to explore this style up until the time he emiraged. Together with his Jewish wife, whom he married in 1972 and his two children, he was officially allowed to leave for Israel - where he never arrived. He remained for one and a half years in Vienna, the home of his publisher in the west, and he took Austrian citizenship. Then he moved to West Berlin.

"To write I must prepare myself for a long time.

Sometimes it takes five years,

And then I come up with many pieces

In a very short time."

Fratres, Cantus in memory of Benjamin Britten, Tabula rasa came out of Arvo Pärt's creative silence in the years 1974 to 1976.

Fratres

Fratres is dated 1977 and was first performed by the Estonian ensemble of early music "Hortus musicus". On a commission from the 1980 Salzburg Festival, Arvo Pärt wrote variations on the theme of this composition. These were performed by Gidon and Elena Kremer - to whom the work is dedicated - on August 17, 1980 in Salzburg. Later in Berlin, Pärt wrote a version of the piece for The Twelve Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic which came closer to the original composition: music for three voices above a pedal point for seven early or modern instruments and percussion.

In the original version as well as in cello arrangment the pedal point - the open fifth A-E - was sustained throughout the entire piece. In the variations, which have added an independent violin prelude at the beginning, the two-measure percussion inserts have been replaced by piano chords and new intervals have replaced the pedal point. In the initial version, the work's six-measure theme is repeated nine times, coming in often a minor or major third lower - yt is repeated eight times in the cello version. The sequence of entrances yields the scale e-c-a-f-d-b-g-e-c sharp. In one instance,

this pattern of six measures is interrupped by two 6/4 percussion measures, in another instance bya a two-measure piano ostinato. With in the theme, the sequence of 7/4, 9/4 and 11/4 measures corresponds to the principle of adding on - and the theme's melodic structure is developed according to thi principle.

The schematic of this composition, its numerical relationships, and its easily discernable syntax give the effect of a semi-transparent screen. One can easily enter in to it, but in doing so the work does not begin to give itself away.

Cantus in memory ot Benjamin Britten

The orchestra piece Cantus is dedicated to the memory of Benjamin Britten. " In the past years we have had many losses in the world of music to mourn. Why did the date of Benjamin Britten's death - December 4, 1976 - touch such a chord in me? During this time I was obviously at the point where I could recognize the magnitude of such a loss. In explicable feelings of guilt, more than that even, arose in me. I had just discovered Britten for myself. Just before his death I began to appriciate the unusual purity of his music - I had had the impression of the same kind of purity in the ballads of Guillaume de Machaut.

And besides, for a long time I had wanted to meet Britten personally - and now it would not come to that".

Cantus: a personal threnody: an ultimate closing chord: a mystical, threshold experience.

Tabula rasa

"To a certain extent, Tabula rasa was Gidon Kremer's suggestion. I am always afraid of a new ideas. I said to Gidon, 'do you think it could be a slow piece?', Gidon said 'yes, of course'. And the piece was finished rather quickly. The orchestration recalls a piece by Alfred Schnittke which was to be performed at the same time in Tallinn. It is for two violins, prepared piano and strings. When the musicians saw the score, they cried out: 'Where is the music?' But then they went on to play it very well. It was beatyful; it was quiet and beautiful."

What kind of music is this? Whoever wrote it must have left himself behind at one point to dig the piano notes out of the earth and gather the artificial harmonics of the violins from heaven. The tonality of this music has no mechanical purpose. It is there to transport us towards something that has never been heard before.

Wolfgang Sandner

ecm records, from "tabula rasa"

|

|

|

|