|

|

|

|

|

|

| On the Threshold to Paradise |  |

|

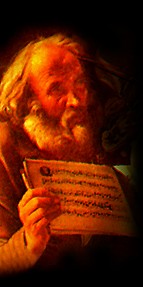

The Kanon pokajanen by Arvo pärt is based on the canon of repentance, which already appears in the earliest Church Slavynic manuscripts. St. Andrew of Crete (c.660-740n AD), whose main composition is the well-known Great Canon, is also credited with having written this work. In the Greek-Russian Orthodox Church, the canon is part of the morning office, whose message is the appearance of Christ in the world. One rises to meet the coming of Light, which will later shine in full glory in the liturgy. In monasteries, the canon is still sung at the break of day; in parish churches, however, it is now sung the preceding evening.

The canon is a song of change and transformation. In the symbolism of the church, it inokes the border between day and night, Old and New Testament, old Adam and new Adam (Christ), prophecy and fulfilment, the here and the hereafter. Applied to a person, it recalls the border between human and divine, weakness and strength, suffering and salvation, mortality and immortality. The symbolic reference to borders is especially powerful what the canon is sung in church. We may picture it as follows: The canon is heard in the nave, barely illuminated by the flickering candles, while the door to the sanctuary still remains closed.

As soon as the canon has come to an end, this entrance, the "door to paradise" or the "royal door", as it is called, opens. The church is filled with light, signifying the presence of Christ.

In the canon of repentance, the text is devoted to the theme of personal transformation. Repentance appears as a necessary threshold, as a kind of purification on the way to salvation in paradise. This borderline situation is a challenge to the human soul. The soul is underway, and the difficulty of following stanzas, that is, between the praise of the Lord and the lamentation of one's own weakness. The desire to find a link between these levels is expressed in the brief words of the refrain.

Thus the canon of repentance becomes the lamentation of Adam, who is weeping at the closed door to paradise, repenting of his sins and imploring Christ for redemption, that is, for admission into the lost Paradise.

|

| Kanon Pokajanen |  |

|

Many years ago, when I first became involved in the tradition of the Russian Orthodox Church, I came across a text that made a profound impression on me although I cannot have understood it at the time. It was the canon of repentance.

Since then I have often returned o these verses, slowly and arduously seeking to unfold their meaning. Two choral compositions (nun eile ich

., 1990 and Memento, 1994) were the first attempts to approach the canon. I then decided to set it to music in its entirety-from beginning to end. This allowed me to stay with it, to devote myself to it; and, at the very least, its hold on me did not abate until I had finished the score. I had a similar experience while working on Passio.

It took over two years to compose the Kanon pokajanen, and the time "we spent together" was extremely enriching. That may explain why this music means so much to me.

In this composition, as in many of my local works, I tried to use language as a point of departure. I wanted the word to be able to find its own sound, to draw its own melodic line. Somewhat to my surprise, the resulting music is entirely immersed in the particular character of Church Slavonic, a language used exclusively in ecclesiastical texts.

The Kanon has shown me how much the choice of language predetermines the character of a work, so much so, in fact, that the entire structure of the musical composition is subject to the text and its laws: one lets the language "create the music." The same musical structure, the same treatment of the word, leads to different results depending on the choice of language, as seen on comparing Litany (English) with Kanon pokajanen (Church Slavonic). I used identical, strictly defined rules of composition and yet the out-come is very different in each case.

Arvo pärt

Translation: Catherine Schelbert

|

|

|

|